Four PhD candidates from Monash University, who are already Doctors of the medical kind, are conducting research on a rare and debilitating neurological illness affecting the Australian population.

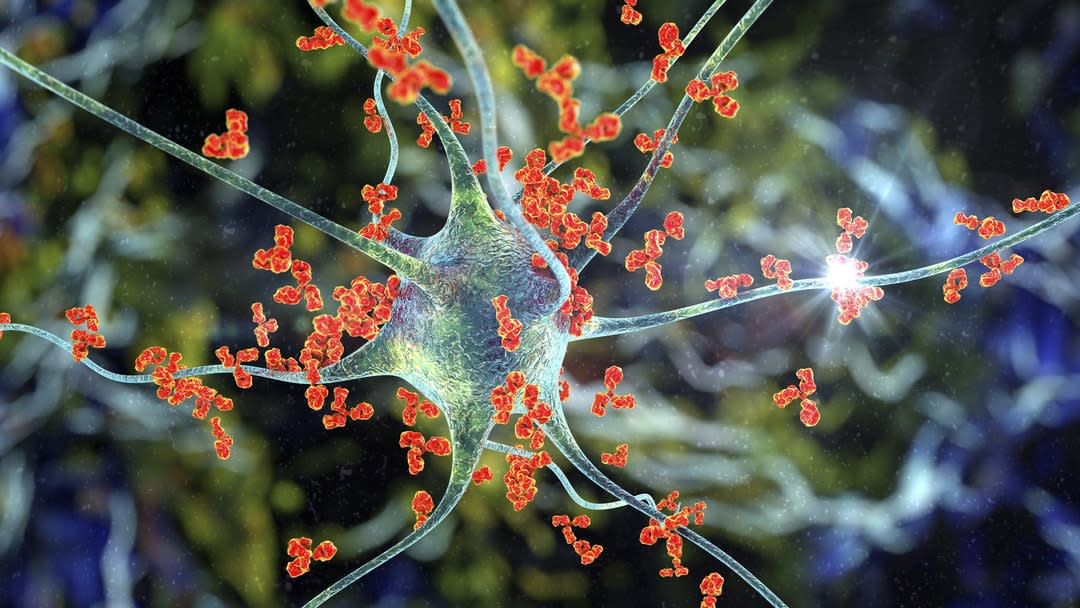

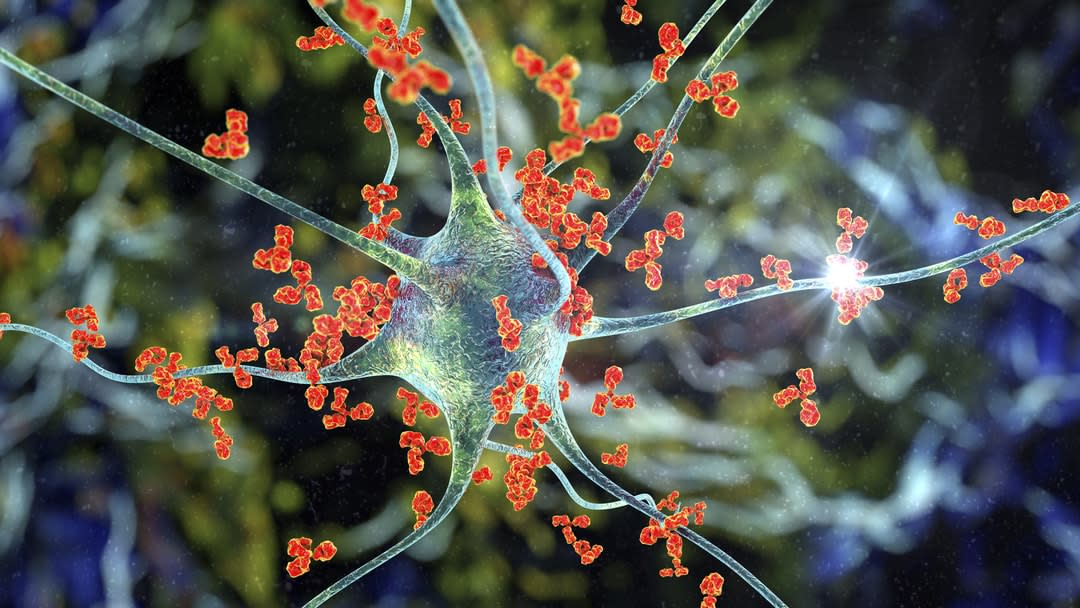

It’s described as feeling like your brain is on fire. People with autoimmune encephalitis (AE) are often misdiagnosed as suffering from a psychiatric illness, delirium or dementia. The condition can mimic many other diseases, and hence there can be delays in diagnosis resulting in brain damage and a largely poor prognosis. The patients can be young or old, and the burden of misdiagnosed, late diagnosed or wrongly diagnosed disease can be high.

The disease – only recognised in the past 12 years – is the focus of a national clinical study led by Dr Mastura Monif at the Monash University Department of Neuroscience, in the Central Clinical School.

Patients diagnosed with AE can go from a psychiatrist to a physician (neurologist, geriatrician, general physician, general practitioner) and back again, with each potentially wrongly diagnosing them with a psychiatric illness, delirium, dementia or otherwise.

Last year, Netflix aired a film, Brain On Fire, about the true story of Susannah Cahalan, a New York Post journalist, as she falls ill with AE and is repeatedly misdiagnosed until the mystery is solved by a doctor called Souhel Najjar.

It is estimated that 3500 Australians are living with the disease.

There are various types of AE – one type generally affects females of reproductive age who may have an ovarian teratoma (ovarian tumour), and while mounting an immune response to the teratoma their immune system aberrantly attacks their own nerve tissue. This can result in behavioural change, psychosis and seizures.

Other forms of autoimmune encephalitis can occur in males or females of various age groups, and can impose detrimental consequences to their wellbeing.

People with AE can present with acute psychosis, abnormal behaviours and personality change, delusions, hallucinations, memory loss and seizures – symptoms that are in fact a consequence of an autoimmune disease like type I diabetes or multiple sclerosis rather than a pure psychiatric illness.

Dr Monif said that the national study into AE – which has started recruiting patients – will register patients with AE and follow them for up to four years. The study was recently awarded a $2 million Medical Research Futures Fund grant to investigate clinical, neurological, radiological, immunological and cognitive and neuropsychiatric biomarkers of disease subtype, as well as markers that determine treatment response.

Dr Monif is supervising four PhD candidates who are focusing on various arms of the project.

PhD candidate and neurologist Dr Robb Wesselingh is investigating seizure profiles and peripheral blood immunological biomarkers of disease. PhD candidate and neurology fellow Dr James Broadly is focusing on imaging abnormalities (CT scans and MRI scans) to see if certain abnormalities on brain scans can translate to different outcomes. PhD candidate and neuropsychologist Sarah Griffith is focusing on the cognitive and neuropsychological aspects of AE.

“We aim to develop a cognitive profile to hopefully aid with diagnosis, as well as working out the cognitive sequelae of the disease so that patients and their carers can be advised on what they can expect,” Griffith said.

“If diagnosed early, and treated with steroids/immunotherapy, these patients could be given back a potentially better prognosis.”

PhD candidate and neurology/epilepsy fellow Dr Tracie Tan is examining prolonged seizures (status epilepticus) and drug-resistant seizures that can occur in patients with AE.

A large biobank is established at Monash Department of Neuroscience, which will be storing samples of blood and CSF fluid (cerebrospinal fluid, which contains markers for AE) and measuring samples of a protein, called P2X7 Receptor, which is known to be a marker of brain inflammation.

The team will examine various other novel biomarkers of disease, as well as determining clinical factors that would favour a better response to treatment.

The research team is also looking at 173 retrospective cases of the disease (diagnosed in various centres in Victoria in the past 10 years) to look at ways of detecting the disease earlier.

For the prospective arm of the study, which aims to recruit more than 100 patients, each patient will be reviewed on an at least six-monthly basis for up to four years.

This is the longest and most comprehensive study of AE globally.

Long-term consequences are the current norm

Currently, according to Dr Monif, almost all patients with AE suffer long-term consequences of the disease, from some cognitive impairment, to lifelong need for physical and mental care.

“If diagnosed early, and treated with steroids/immunotherapy, these patients could be given back a potentially better prognosis,” she said.

Dr Monif believes that the trial and the creation of the Australian Autoimmune Encephalitis Consortium will raise the profile of the disease so that anyone presenting with the symptoms of AE are triaged accordingly, and with timely investigations the disease is diagnosed promptly.

The consortium brings together national experts (neurologists, epileptologists, radiologists, psychiatrists, neuropsychologists, immunologists, neuroscientists, neuro ophthalmologists, and biostatisticians) from Victoria, NSW, Tasmania and Queensland to collaboratively tackle the problem of AE facing the Australian community.

This article was first published on Monash Lens. Read the original article

2 comments

I would love to discuss this condition with someone from the research team.

Hi Maura, the researcher can be contacted via email see here https://lens.monash.edu/@mastura-monif