Dr. Harry Rolf, Research Associate

Australian Studies Institute (AuSI), Australian National University

Book review of Margaret J Robertson (2019), Power and Doctoral Supervision Teams: Developing Team Building Skills in Collaborative Doctoral Research, Routledge.

Power and Doctoral Supervision Teams by Dr Margaret Robertson drew my interest following my own foray into the landscape of doctoral education where I have been studying collaboration by doctoral students. It is not a book that one easily comes across, nor sits down to read. The academic language, concepts of power and even the doctoral journey itself require the reader to have a prior understanding or experience of the subject to get the most out of this insightful study.

Robertson’s work is deserving of greater visibility, and making the knowledge more accessible is a motivation for writing this review. Her book provides an important opportunity to consider the role, value and complexity of the power dynamics at play within supervision teams and their relevance to a successful PhD.

Context

Traditionally supervision in doctoral education has been an arrangement between a doctoral student and a supervisor, where a senior academic with expertise in a relevant discipline will provide guidance. While this practice of solo supervision continues, supervision practice is changing. It is now common for a doctoral student to be supervised by a team of researchers, a change that reflects the increasing importance of teams in modern research practice.

Research teams both large and small bring together the diverse expertise needed for innovation, impact and to solve ever more complex problems, but in doctoral education teams change the dynamics of power among supervisors and doctoral students, opening new opportunities and challenges in pedagogies of doctoral education.

The book offers a much-needed examination of the dynamics of power in doctoral supervision teams. It responds to a significant development in Australia’s research training policy over the last decade, the requirement for each doctoral student to have at least two supervisors which has given rise to ‘team’ supervision at Australian universities. Team supervision is now embedded in the Australian Higher Education Standards Framework.

Navigating power

In the book, Robertson delves into the dynamics of power in supervisory teams from the perspective of the Social Sciences, Humanities and Education disciplines. Drawing on interviews with supervisors and doctoral candidates, the book offers readers a theoretical and practical understanding of how different interpretations and configurations of supervision teams can empower or disempower team members.

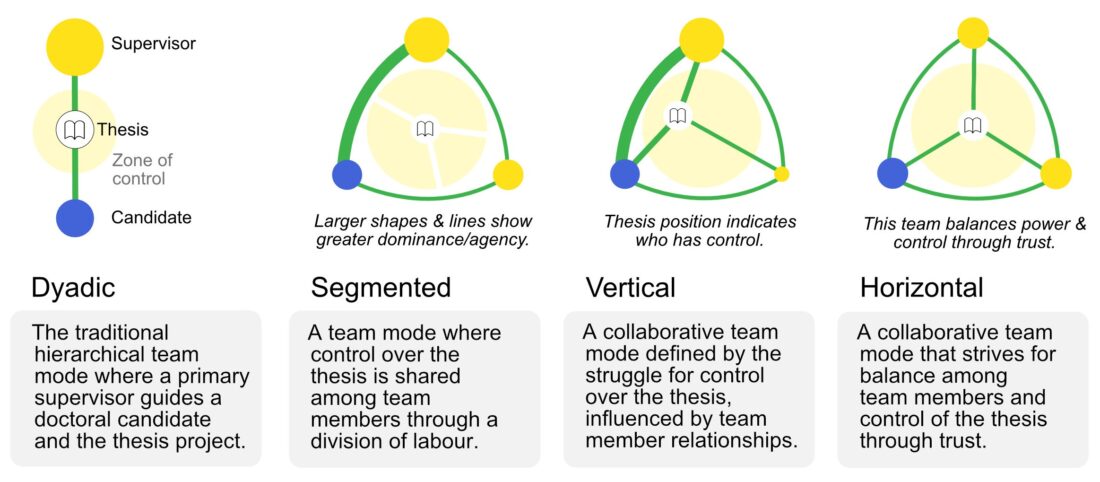

Four domains of power – governance, pedagogy, interpersonal relationships, and desires are examined, with a significant focus placed on the domain of governance. Analysis looks at individuals’ capacity to achieve their preferred outcomes and exercise agency in different team modes that include dyadic (traditional), segmented or collaborative (hierarchical or horizontal). In doing so Robertson demonstrates how the structuring and interpretation of policy defines the social positions of team members, how the structure of a team affects the dynamics of power within a team, and the forms of power available to team members.

A key insight is that a doctoral supervision team is not static, teams change throughout candidature both in terms of membership and mode for many reasons. As they do, so too do the power dynamics. Robertson is able the bring these team dynamics to life through the thoughtful curation and discursive engagement with supervisors’ and doctoral students’ stories that illustrate the different circumstances that can arise.

The illustration (below) highlights differences between the four team modes, which are defined by stronger or weaker relationships between team members and the distribution of power (dominance), agency, and control over the thesis.

Guidance

Robertson’s insights are used to provide guidance in two forms, pedagogy for collaborative team supervision and practical tips for the doctoral supervision journey. In terms of pedagogy, Robertson identifies that strategic team communication is critical and that a pedagogy of conversation can create a rich environment for knowledge creation and transformational learning within a team.

Practical tips for candidates and supervisors are as follows:

- Take time to understand the doctoral education policy context at your university including supervision, expectations and the support services and resources available.

- Choose team members carefully, knowing at least one team member in advance is advantageous and meeting potential team members is essential.

- Plan to negotiate the team mode that works best for you and your desired outcomes.

- Establish a strategy for team communication, clarifying expectations and roles.

- Regularly review team function, keep an ongoing conversation about team practice on the meeting agenda.

- Reach out to doctoral students or supervisors for support and be willing to share your knowledge.

- Be prepared for change.

Power dynamics within supervision teams

Insights into the power dynamics of teams are also relatable to the broader study of teams (team science) and there is a much more complex story to be told about how insights fit within this multi-disciplinary body of knowledge.

In this regard the book could have gone further, and it left me pondering some unanswered questions: to what extent do team dynamics vary when a thesis is produced by or with publication, what effect do external collaborators such as co-authors or end-users have and what about the diversity of team members?

Robertson’s findings did reveal that rank (seniority), experience, age and gender are relevant to the power dynamics of supervisory teams, these characteristics were woven throughout the stories of doctoral candidates and supervisors.

Team diversity is known to be beneficial in all its forms, such as gender, age, ethnicity, internationality, institutional or disciplinary diversity. Research shows that a balance of diversity, knowledge and experience in a research team can improve productivity, impact and the quality of research. While characteristics such as workload and experience are prioritised in the selection of supervisory team members by policy, supervisors and advice to doctoral students, diversity should also be considered.

In conclusion

There is a lot of advice available to doctoral candidates and supervisors on how to undertake a PhD, but there are few resources available that successfully ground their guidance with theory and evidence as Robertson has done. The book charts a clear path through the complex landscape of supervisory teams and offers guidance that is relevant to doctoral supervision teams in all disciplines. The book makes an important contribution to the literature available to doctoral candidates and supervisors by tackling an underrepresented yet critical aspect of the PhD – the supervisory team.

1 comment

Looks interesting. One glaring issue is supervisory promotion of candidate knowledge offering to faculties without scholar community mechanism in place and eventuating use of candidate work for own profit under the guise of overarching undeclared study group learnings, coincident to bullying behaviours associated with the actions and evading offer of consideration or permissions to use. In the case of practice reflection PHD models and that assuming peer supervisory role, that is a major problem that appears to threaten the very point of the leadership role and model. No one would enter such risk knowing the risk outcome. But in this underlies a problem with RITE course whereby a video articulating ethics noted co-authorship as complicated- it certainly should be clear and simple and uphold concept of agreement, moral rights and respect. Interested to see if this type of issue is addressed in the book.